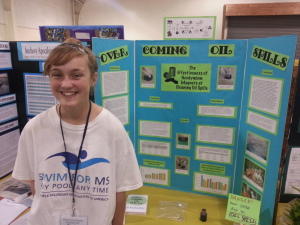

We really enjoyed a month without seizures, especially as it included Spring Break! We went to central Florida, where we enjoyed visiting Kennedy Space Center, St. Augustine, and Disney World. We also visited Crystal River, home to many wild manatees. At a refuge there we found the actual manatee that Rachel had adopted following her 8th birthday party. Rachel had asked for donations to Save the Manatees instead of presents, and one of the boys brought his piggy bank to the party to empty into Rachel’s donation jar!

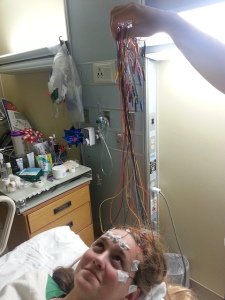

The no-seizure month came to an end in mid-April. After two seizures within a week, we called her neurologist. She doubled the dosage, to one pill in the morning and one pill at night.

Unfortunately, this didn’t seem to help much, and Rachel continued to have seizures into May.